4 Reasons Your 8-12 Year Old Should Start a Performance Training Program Now – Part 1 of 2

by David Justice

“When should my son/daughter start doing more than just games, practices, and private lessons?”

That’s a question we get fairly often at AYC Health & Fitness when speaking to parents of some of our younger clients. The truth is, the answer isn’t going to be the same for any two children. Physically, experts say that somewhere between the ages of 8 and 12 is a good starting point to begin teaching proper movement patterns and introducing lighter levels of resistance training in an effort to improve sports performance.

The key variable however lies more on the mental side – how mature are they for their age? Many within the fitness industry agree that as long as a child is capable of listening to instructions and following orders, they are more than ready to go in this regard.

Today’s post will be the first of a two-part series focused on determining why I believe an organized strength and conditioning program is a great component to add to a child’s weekly routine if they are looking to really take their game to the next level (both now and in the future).

Included below are four reasons that a program of this nature will benefit your child PHYSICALLY. Part Two will then delve deeper into the MENTAL side of how this will aid in your child’s performance on and off the field.

“Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world.

He who understands it, earns it … he who doesn’t … pays it.”

-Albert Einstein

I really like that quote because the concept of compound interest was the first thing I thought of when I decided to write about this topic. While it typically refers to investing for retirement and other financial goals, it rings true when it comes to physical fitness as well. The more hard work you put in at an earlier age, the better prepared you will be when you are older.

There are a multitude of ways an organized strength and conditioning program can benefit a youth athlete. Several of those include how it creates good habits and promotes a healthy lifestyle, establishes a foundation of athleticism, improves performance on the field, and uses scientifically proven data to take advantage of specific windows of opportunity to help maximize athletic potential.

- It creates good habits and promotes a healthy lifestyle

This isn’t necessarily the most relevant to playing sports at a high level several years down the road in high school (and possibly college), but it’s at the top of my list for a very important reason.

Kids and teens these days weigh more than ever before thanks to poor nutrition and increasingly sedentary lifestyles that are enabled by the vast use of electronics and modern conveniences at our disposal. According to the American Heart Association, “about one in three American kids and teens [are] overweight or obese,” a number that has “more than tripled from 1971 to 2011.” This epidemic has surpassed smoking and drug abuse and is now the #1 health concern among our nation’s parents.

One way to reverse that trend is to get our kids up and moving more often. The CDC recommends children get at least 60 minutes of physical activity every day of the week, including some form of “vigorous-intensity aerobic activity” on at least 3 of those days.

Adding in a properly designed sports performance program not only qualifies for the “vigorous-intensity aerobic activity” component, but it also:

- Builds healthier bones and muscles

- Prevents disease

- Promotes good sleeping patterns

- Reduces stress and increases happiness

It will also more than likely instill a sense of confidence in your child in and out of the gym. Additionally, your child will begin to learn about the values of hard work, commitment, punctuality, and teamwork at a young age. These are all qualities that will come in handy as they continue climbing the ranks of their sport and begin playing against increasingly more challenging levels of competition.

- It helps the develop a much-needed foundation of athleticism

Unstructured play time is essentially a thing of the past. According to internationally recognized strength coach, speaker, and writer Dr. John Rusin: “Over-coaching, overtraining, and over-specialization” is hurting your kid’s athletic development.” With the recent surge in popularity of specializing in a single sport at a young age, everything these days tends to be a game/competition or a practice for that same activity.

When you put all your eggs in one basket like that, you begin to encounter the following:

- Increased risk of injury

- Increased risk of burnout

- Decreased exposure to movement patterns found in other sports

While the first two points above are self-explanatory, the last one is what I’d like to discuss. Growing up, my main sport was baseball. And I was a catcher. If you think about the day-to-day activities of a catcher, there isn’t a whole lot of movement involved if we’re being completely honest. Therefore, I wasn’t really in a position to be exposed to very many movement patterns that would collectively work in turn to make me more athletic.

While a catcher is somewhat of an extreme example on the movement spectrum, the basic principle applies to almost all other sports in some capacity. For example, basketball players are adept at running, jumping, changing direction, and playing at an upbeat tempo both in short spurts and for longer amounts of time. But they are rarely forced to generate rotational power with their lower and upper body.

On the other hand, two of the most important skills in the game of baseball are the ability to hit and/or throw the ball hard. How is that done? By generating rotational power. While baseball players excel there, they aren’t exactly known for their ability to run fast, jump high, or simply be in shape (although a lot has changed in the last 25-30 years).

Long story short, playing as many sports as possible for as long as possible is a good thing. Every sport has a specific set of demands and movement patterns that athletes are exposed to, and the more of them your kid encounters during their formative years, the more athletic they will be.

As I mentioned during my one of my weekly videos (The Top 3 Changes I See During a Youth Athlete’s First Year at AYC ), we spend a lot of time working on making our clients more athletic. I understand the environment for youth athletes these days, and that the trend of specializing at a young age likely won’t be going anywhere anytime soon. So we spend lots of time hopping, skipping, jumping, and performing a variety of other explosive movements to help ensure they are seeing things from an athletic standpoint they might not otherwise see out on the playing field.

- The athletes who dominate are usually the strongest and most developed

Have you ever watched the Little League World Series and noticed how there’s one kid every year who dominates the rest of the field? What typically stands about him? Oh yeah, he’s about a foot taller than everybody else and a whole lot heavier to boot.

Do you know why he’s blowing fastballs by everybody and hitting homeruns wayyy over the outfield wall? Let’s get scientific for a minute.

Newton’s second law of motion states that the force (F) acting on an object is equal to the mass (m) of an object times its acceleration (a). Therefore, if you have a 12 year old at the LLWS who weighs 110lbs and another with an identical skillset weighing in at 175lbs, the heavier one will likely be able to throw the ball harder and hit it further (with all other variables remaining constant) due to his ability to generate more force thanks to his advantage in having a larger mass.

The same thing applies to football players. For instance, I was an offensive lineman back when I played on the freshman football team. Standing in at 5’10” and 155lbs, I wasn’t the size of a prototypical lineman at that level. But I wasn’t fast enough to play anywhere else on that side of the ball so that’s where they put me. While I went on the make the “A” team thanks to my knowledge of the playbook and hustle during practice, I would get pushed around by some of the larger defensive lineman simply because they weighed 30, 40, even 50+lbs more than I did.

One game in particular comes to mind. It was against a school that wasn’t well ranked, and we ended up beating them pretty badly. But I consistently needed help from my left tackle double-teaming my assignment because their defensive lineman weighed 300+lbs and I couldn’t slow him down to save my life. To be quite honest, he wasn’t that good, yet despite my doing everything I had been taught to do fundamentally, I couldn’t stop him because he was so much bigger than me.

And that’s just the way it goes sometimes. It’s more prevalent in elementary school and middle school, but you can look at high school C-teams and even some JV teams and get a rough idea of how good a team is more often than not based on how physically developed the players are.

- The “Windows of Opportunity” for athletic development occur earlier than you might think

I don’t want this to sound like it’s the end of the world if your child doesn’t start a structured workout program by a certain age. That isn’t the case at all. But research has proven that there are certain periods of time in a child’s development in which the effect of sports performance training can be maxed out to help them reach their full potential.

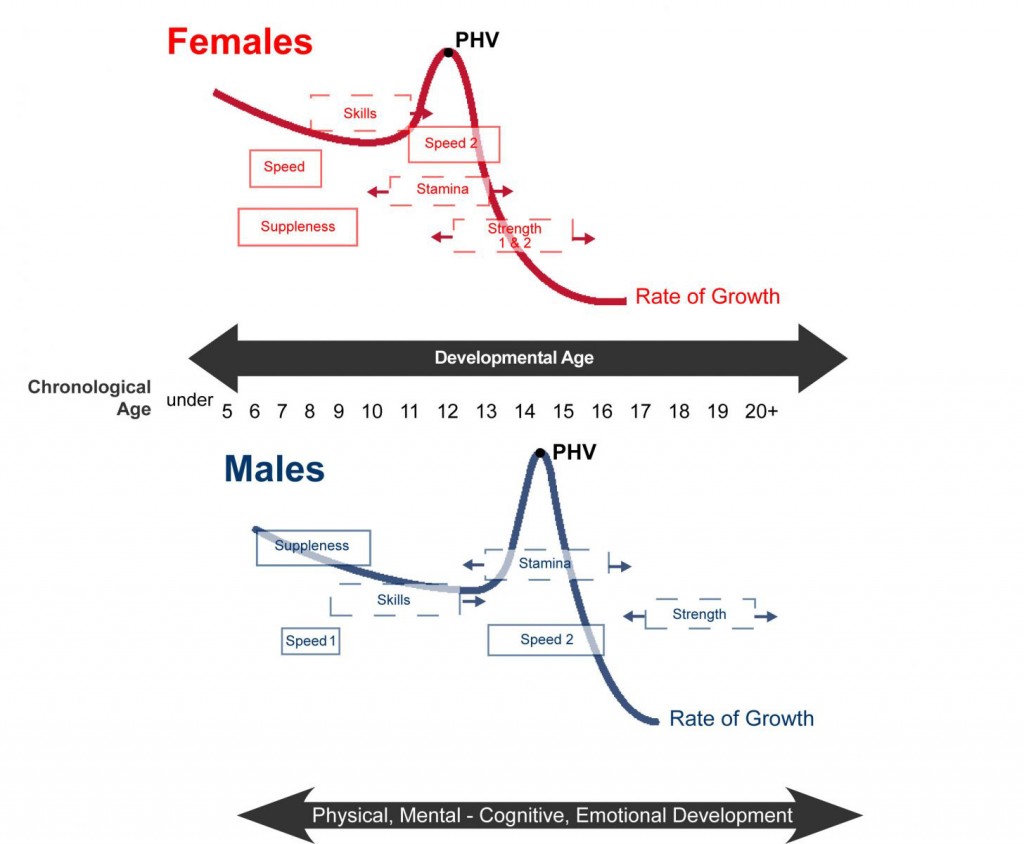

The charts above illustrate the “windows of opportunity” for youth athletes and the ages at which it is easiest for them to reap the maximum benefits of physical development associated with exercise. Once those windows have passed, it becomes far more difficult to make up for that lost time.

From “Windows of Optimal Trainability” (Balyi and Way 2005):

“Windows of trainability refers to the sensitive periods of accelerated adaptation to training, which occurs prior, during and early post puberty. All systems are always trainable, thus the windows are always open, HOWEVER, a window is fully open during the sensitive periods of accelerated adaptation to training and partially open outside of the sensitive periods. There is full consensus among experts in this area that if physiological abilities are not developed during the sensitive periods, the opportunity for optimum development is lost and cannot be fully retrieved at a later time.”

For girls, the first window of trainability occurs between the ages of 6-8. For boys, it’s 7-9. During that timeframe, an athlete can actually influence the makeup of their muscle fibers and basically alter their genetic makeup.

The second window of trainability hits right around puberty for both genders. In girls, it’s between the ages of 11-13. In boys, it’s 13-16.

And that’s it for today! As always, if you have any questions or comments feel free to contact by phone at 913.593.1708 or via email at David@aycfit.com.

If you, or your child, are committed to improvement, our Sports Performance Program may just be the perfect fit.

We utilize a Small Group Personal Training setting with no more than 4 athletes training together at a time. This allows us to provide plenty of individual attention along with customized workouts tailored to the goals of each individual.

These sessions take place 6 days per week and are ongoing so you can start at any time.